About the Project

Transnational Policy Dialogue for Improved Water Governance of Brahmaputra River

Rivers have always held a significant position not only for the prosperity of the civilizations but also for religious and cultural identities that they provide. Rivers within India have been likened to deities and revered in their naming accordingly. Among the several major rivers of India, Brahmaputra, which necessarily means ‘Son of Brahma’, is the only river in India with a male identity.

Rivers have always held a significant position not only for the prosperity of the civilizations but also for religious and cultural identities that they provide. Rivers within India have been likened to deities and revered in their naming accordingly. Among the several major rivers of India, Brahmaputra, which necessarily means ‘Son of Brahma’, is the only river in India with a male identity.

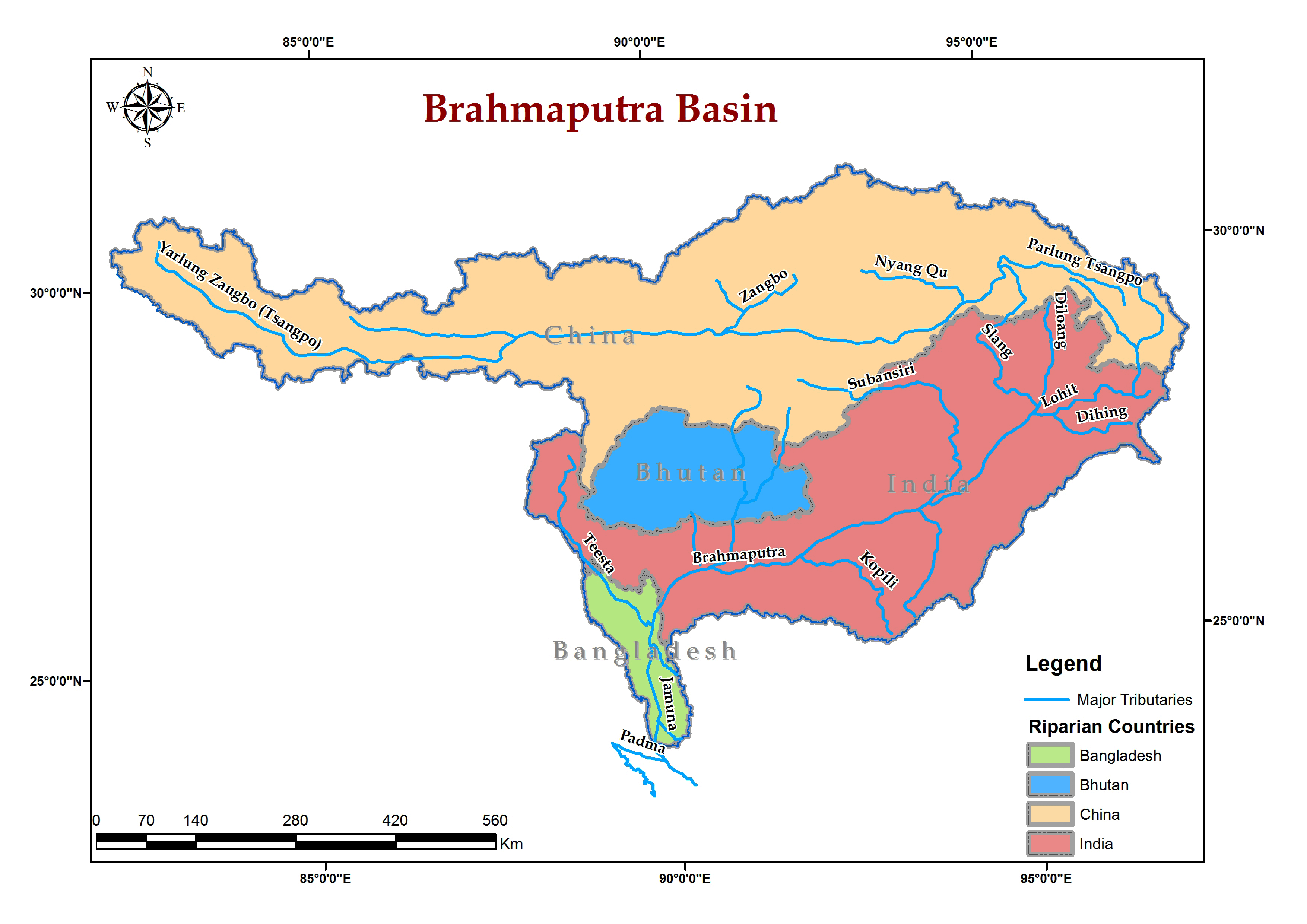

Brahmaputra originates as the Yarlung Zangbo River in southern Tibet, also known as Tsangpo (meaning ‘The Purifier’ in Tibetan), from a massive glacier near Mansarovar Lake in the Kailash range at an elevation of around 5,150 m above mean sea level. The river then penetrates through the Himalayas and flows through Arunachal Pradesh in India as the Dihang or Siang River, winding out of the mountains. Then it flows southwest in the Assam valley as the Brahmaputra or Lohit and merges with Ganga (or Meghna in Bangladesh), when the river flows south towards Bangladesh as the Jamuna river. Transboundary water (TBW) bodies act as a source of potential growth and development by creating hydrological, social and economic dependency among the basin communities and the riparian nations at large. Therefore, the focus of their governance should ideally be centered on collaboration and cooperation.

The region has many significant and often related social challenges which include floods and water scarcity; population growth and poor infrastructure; food insecurity and poverty; social uprising and insurgency; labour migration; ethnic minority disenchantment; unsustainable traditional land use practices; HIV-AIDS and other public health problems; border disputes and resource conflicts.

The basin is inhabited by many indigenous people, who have traditionally engaged in nomadic and agro-pastoralist practices in the upstream regions of Tibet, China, shifting cultivation in the upper-middle in northeast India, terraced agriculture in the middle mountains of Bhutan, and intensive rice paddy and fish cultivation in the downstream reaches in Bangladesh. The total water supply in the basin varies from 1,700 to 4,000 m3/yearper person, indicating adequate water availability throughout the basin. However, the basin is characterized by large seasonal fluctuation in water availability due to the very wet monsoon and the extremely dry winter.

The issue of hydropower has also acquired great significance in the area. For example, about half of Bhutan’s national revenue depends on hydropower that is generated from water contributing to the flows of the basin. In total 11 large dams larger than 60m or with an installed capacity of more than 100MW are currently under construction or are being planned. The Brahmaputra mainstream is also navigable in the lower parts in Bangladesh and India (mainly Assam) and in that way also serves as an economic corridor.

Key challenges for sustainable management of the basin include conflicts over water, which are increasing both within and between countries. Conflict is looming largely over sustained growth in water and energy demand, interference with natural river flows from dams, inter-basin water transfers, water diversions, deforestation and floods, altered sediment and nutrient loads. Livelihoods are already impacted by changes to hydrology from erosion and to the ecology from deforestation and plantation. Food production systems, cultural identity, rural economies have all seen dramatic changes in recent years, with more changes likely in the time to come. Among the most powerful contemporary forces shaping both local cultures, livelihoods, land-use and ecosystem are various government policies and the expansion of regional, national and international markets. A dialogue between the different stakeholders from neighboring countries is critical for the smooth functioning of the basin.